When I discuss American spending habits, I try to cite specific numbers. Sometimes people write to ask where I get my info. Simple. Whenever I cite figures about American earning, saving, and spending, I get them from the U.S. government. In particular, I use the Consumer Expenditure Survey (or CEX) from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Here’s how the BLS website describes the Consumer Expenditure Survey:

The Consumer Expenditure Survey program consists of two surveys, the Quarterly Interview Survey and the Diary Survey, that provide information on the buying habits of American consumers, including data on their expenditures, income, and consumer unit (families and single consumers) characteristics. The survey data are collected for the Bureau of Labor Statistics by the U.S. Census Bureau. The CEX is important because it is the only Federal survey to provide information on the complete range of consumers’ expenditures and incomes, as well as the characteristics of those consumers.

The Consumer Expenditure Survey is the only reliable source I’ve found about actual spending habits. Most similar projects have much smaller sample sizes and provide theoretical numbers. The CEX is a great way to develop a descriptive budget (one that deals with real behavior) instead of a customary budget (one that pushes an agenda).

Naturally, the CEX has its drawbacks. As always, averages (and medians) only provide a limited view of a dataset. Plus, what might be true for an entire population (a country, in this case), probably isn’t true for a small subsection (your state or city, for instance). Still, for looking at the Big Picture, nothing I’ve found beats the Consumer Expenditure Survey.

Because I’m a money nerd, I get very excited when the new Consumer Expenditure Survey numbers are released each year. And guess what! The 2018 data was released two weeks ago. I spent some time yesterday sitting in the hot tub and geeking out over U.S. spending stats on my iPad. Then I updated my personal CEX spreadsheet. (What? You don’t have one of your own?)

Let’s take a closer look at the Consumer Expenditure Survey — and what we can learn from it.

Decades of Data

If you visit the BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey page, you’ll likely be overwhelmed by the amount of information available. When I first found the site, I had to sort through the various reports until I found the one most useful for my work: the “age of reference person” table, which splits spending info based on the age of the person surveyed. (This is the base report I use when I collect stats.)

I also like the “Library” section at the Consumer Expenditure Survey website. It contains decades-worth of research papers and reports related to personal spending. Some of my favorites include:

To a money nerd like me, this stuff is golden!

Like most federal government agencies, the BLS has an excellent website. For starters, you can access all past CEX data on one of two pages: tables from 1984 to 2011 (plus 1961 and 1973), tables from 2012 to 2018.

Turns out the government performed this survey once during the early 1960s, once during the early 1970s, then made it an annual thing starting in 1984. That means there are now nearly fifty years of stats for money geeks to sort through. (Plus, the site provides access to a “forgotten” expenditure survey from the early 1940s!)

I’ve created the following table, which points to individual reports for each year. Yes, this is mainly for my own personal nerdery, but I hope that at least a few of you money bosses will enjoy it also.

Crunching the Numbers

A few years ago, I went through past editions of the Consumer Expenditure Survey to grab data for a spreadsheet that tracks how American spending has evolved. Naturally, I just updated it for this year.

Rather than bury myself (and you) in a flood of information, I decided to look at roughly ten-year intervals. I figure by skipping a decade, we get a more meaningful look at shifting habits. That means I used expenditure tables from 1961, 1973, 1988, 1998, 2008, and 2018 — the most recent year for which data is available. For fun, I also included data from the “forgotten” 1941 survey (which is much less comprehensive than later reports).

When I get time this winter, I’m going to update the spreadsheet to contain data for every year of the CEX.

Note: For our purposes, I cut a lot of cruft when transferring these numbers to spreadsheet format. These are complex statistical reports, and they’re filled with numbers we don’t care about (do we need to know the standard deviation for everything?) and jargon that just confuses, such as “consumer unit” (which we’ll call “household”) and “reference person” (which we’ll call “head of household”).

Here’s a complete glossary of CEX terminology. Also, I’m not going to break down every little subcategory. The “Food at home” subcategory has 25 sub-sub-categories beneath it, including “bakery products”, “fish and seafood”, and “processed fruits”. I’m just going to stick to the primary categories and subcategories.

The following tables provide a run-down of the data I collected. After I show you the numbers, I’ll discuss a few things that stood out to me about how American spending has changed with time.

Take some time to browse this info. Let it soak in. Look for patterns. Look for changes. What surprises you about how Americans spend their money? Where do we spend less than you thought we would? Where do we spend more?

Before I point out some of the things I find interesting, you should know a couple of things:

- First, the tables from the 1961 Consumer Expenditure Survey contain wildly contradictory information. Different tables supply different numbers. Sometimes when you add subcategories, the total is greater than the parent category. Where there’s conflicting info, I used table B-17 as my guide (since it most closely resembles later CEX reports). Another problem? Sometimes the scanned pages are challenging to decipher. Is that a three or a five? Six or an eight? I think the numbers here are accurate, but there could be errors.

- The CEX tax calculation changed in 2013. Before then, tax numbers were getting corrupted by “non-response errors.” So, the BLS changed how they calculated taxes to get greater reliability. But, as a result, taxes for 2013 aren’t like any other year in the survey’s history. And taxes in years from 2014 on can’t be compared to 2012 or before. (For more info, check out the Consumer Expenditure Survey FAQ.

With those notes out of the way, let’s dive into the numbers! Let’s look at how Americans spend their money — both now and in the past.

A note on inflation: Using 2018 as a base, I calculated a cost-of-living adjustment for each year in order to factor out inflation. (I used the U.S. government CPI inflation calculator to get these numbers.) Looking at Table 1, you can see that prices in 1988 were roughly 48% of what they were in 2018. After computing this number, I converted it to a multiplier to get inflation-adjusted expenses. If 1988 prices were 48% of 2018 prices, that means we have to multiply numbers from the former by 2.08 to get equivalents for today.

How Americans Spend Their Money

We could spend hours sifting through this information to find patterns and trends. Instead, let’s just hit the highlights.

First up, note how the size of the average household has dropped from 3.2 people in 1961 to 2.5 people in 2018. Almost the entirety of that drop comes from the fact that we’re having fewer children. In 1961, the average household contained 1.2 children; today, it contains 0.6 children.

Meanwhile, automobile ownership has boomed. Since 1973, we’ve gone from owning 1.3 cars per household by to owning 1.9, an increase of 46% during the past 45 years. Other notable demographic changes:

- Today, there are more full-time earners per household than there were in 1961 (1.3 vs. 0.8).

- We, as a society, are much more educated than we were forty years ago. In 1973, an amazing 21.2% of Americans didn’t have a high school diploma. Today, that number is down to 3%. Meanwhile, far more people are attending college (28% in 1973 vs. 67% in 1998).

- Home values have far outpaced inflation. The average home was worth $76,156 in 1973 (inflation-adjusted); today, it’s worth $198,612. But if you look at the tables, you can see the housing bubble in there. Look at the numbers for 2008!

Moving on to Tables 4 and 5 (Income, taxes, and spending), you can see that even when adjusting for inflation, household income doubled between 1941 and 1973. In the past 45 years, household income has only increased by another 24%. It’s fun to speculate about causal relationships for these numbers. I suspect that household income skyrocketed after World War II due to women entering the workforce. (But admit I could be wrong.)

As much as income has increased, spending has grown more quickly. In 1973, Americans spent 85.0% of their after-tax income. In 2018, they spent 91.1% of their after-tax income. (Admittedly, spending as a percentage of income seems to bounce around.)

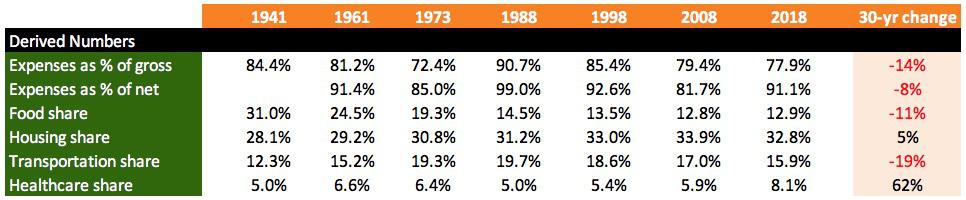

To make it easier to visualize some of these changes, I created another table to calculate some important ratios and percentages.

In 1941, the average American family spent 31% of its budget on food. In 2018, the average family spent 12.9% of its budget on food. That’s a huge decline! From 1973 to 2018, restaurant spending (food away from home) increased 48% while spending on food at home declined 36%. Overall, food spending declined 30% in in the past 45 years.

For me, it’s more interesting to compare numbers today with numbers thirty years ago. (Thus the 30-year change column in the spreadsheet.)

I’m surprised that when you adjust for inflation, a lot of American spending has stayed relatively flat — or even dropped. We’re spending about as much of our income on housing today as we did thirty years ago. There’s a clear downward trend on our transportation expenses. Our food spending remains flat — even restaurant spending! We spend much less on clothing and (unfortunately) reading. (Although that reading number is probably down because we do most of our reading online.)

Meanwhile, health insurance costs are out of control. Between 1973 and 1988, the average American family decreased its spending on health insurance by 9.3%. But in the past thirty years, rates have shot up 245%. That is insane. No other spending category comes even remotely close. And it’s why I make an exception to my no politics policy to advocate for scrapping our U.S. healthcare system. Any other option would be better and cheaper than what we have right now.

Looking at these tables, what numbers stand out to you? How does your spending compare to the average American family? What worries you about your spending — and the spending of the country as a whole? (And are there other similar surveys and reports I should take into account when writing about consumer spending?)

Author: J.D. Roth

In 2006, J.D. founded Get Rich Slowly to document his quest to get out of debt. Over time, he learned how to save and how to invest. Today, he’s managed to reach early retirement! He wants to help you master your money — and your life. No scams. No gimmicks. Just smart money advice to help you reach your goals.

Recent Comments