For decades, I’ve been a proponent of habit tracking. Habit tracking sounds and feels nerdy to a lot of folks, so many people avoid it. That’s too bad. Habit tracking is a powerful tool that can help you make better decisions about your life.

Let me share an example.

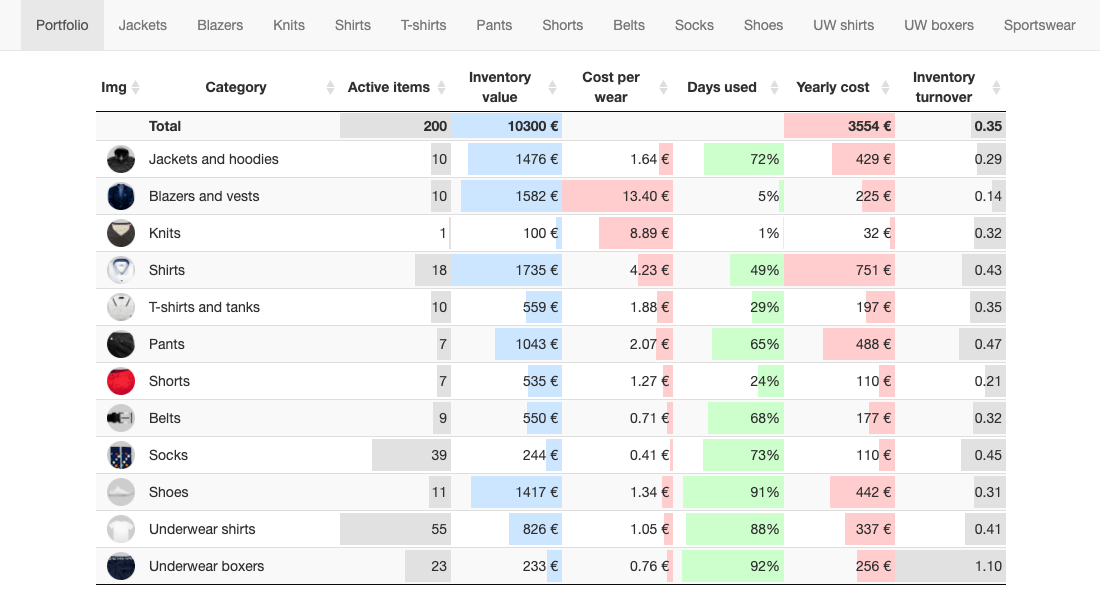

Over at Reaktor, Olof Hoverfält recently published a long piece about why he’s tracked every single piece of clothing he’s worn for three years.

That’s right: For 1000+ days, Hoverfält documented every garment he wore. (And, in fact, he’s continuing to document his wardrobe publicly.) Using the info he collected, he’s now able to make better decisions about which clothes to keep and which clothes to buy. I love it!

Hoverfält says people worry about how much time it’d take to do something like this but they shouldn’t. Most of the time investment is in the initial setup, in that first batch of data entry. Actually using and maintaining the system requires about one minute each day. And the rewards are far greater than the cost in time.

Hoverfält’s project is a perfect example of the power of habit tracking.

The Power of Habit Tracking

For a long time, I’ve preached the importance of tracking your spending. But I think it’s smart to log anything you’re curious about or want to change: your fitness habits, your time habits, your work habits. Documentation is the first step to lasting change.

I recently met my goal to lose thirty pounds in six months, for instance. To succeed, I logged my fitness stats every morning. (And I’ll continue to do so for the foreseeable future.) Kim is starting a weight-loss journey of her own, so she’s logging every calorie she burns or consumes.

And what about tracking your time? All this month, I’ve been using an app called ATracker to log what I’m doing at any given moment. Using the app requires very little effort. The results are interesting. They provide insight into how I actually use my time versus how I think I use it.

That’s the real value of projects like this. Habit tracking allows us to differentiate perception from reality. (In his article, Hoverfält covers this in the section on “actual versus imagined use”.)

I’ve learned that what people think they do (or what they say they do) is often quite different from their actual behavior. “I don’t spend much on clothes,” somebody will say, but when they actually crunch the numbers, they see that their clothes spending is much higher than average. “I don’t overeat,” another person will say, but when they log their calories, they see that their ginger ale addiction adds an extra 500 calories per day to their diet.

Faithful, honest tracking of habits is the only way to truly learn what it is you do with your time and your life.

Here’s another (silly) example of how tracking can help you differentiate perception from reality. A couple of years ago, Kim and I had a disagreement over who cleaned the litterbox most often. She felt like she always did it. I felt like I always did it. We started tracking behavior. We put a sticky note next to the litterbox, and when one of us changed the litter, we made a note. Turns out we were both cleaning the litterbox equally. Disagreement over! The solution to our litterbox problem is to have fewer cats haha.

Don’t Combine Tracking with Judgment

It’s important to keep decisions separate from tracking. When you’re tracking a habit — your spending, your alcohol consumption, your wardrobe use — you want to track actual behavior. Your job at that moment is recorder, not judge.

This is something I’m trying to stress to Kim as she begins logging her food intake. “Don’t beat yourself up over any of this right now,” I told her. “If you eat a cookie, that’s fine. Just write it down.”

If you combine judging with data collection, it’s a recipe for failure. You end up feeling guilty every time you make a poor choice. This makes it so you don’t want to document your behavior. You want to give up. You want to hide.

Habit tracking is only habit tracking. Data collection is only data collection. You’re like an impartial third-party observer who is noting what you actually do and who has not vested interest in whether those actions support your goals or not. In data collection mode, you’re after information — and only information.

![]()

Once you’ve collected enough info, then you can act.

After Kim has documented her diet for a few weeks, she can sit down and look for patterns. Based on these patterns, she can experiment with adopting different habits.

You can see this in my own annual financial updates. I track my spending throughout the year, but I do so only for information. Normally, I don’t try to make course corrections in June or July. But in early January, after I’ve had a chance to crunch the numbers, then I compare how my current habits have veered from my goals. I use this info to make choices like “I want to spend less in restaurants this year” or “I want to experiment with a spending moratorium”.

I’ve found that by keeping documentation and judgment separate, I’m more likely to make changes. Plus, I don’t beat myself up as much. When it comes time to analyze the data, I’m able to do so more rationally because I’m not in the heat of the moment, and I’m looking at a large collection of data instead of individual choices.

The Bottom Line

Okay, you get the point. Habit tracking is a great way to learn what you do with your time, money, and energy. But you need to be sure to keep tracking separate from judgment. Got it. But what about Hoverfält’s wardrobe project? What lessons did he learn?

If you don’t want to read the entire article (although I think you should), here are some quick takeaways:

- “In some cases, buying cheap is provenly more expensive.” This is the boots theory of socioeconomic unfairness. More expensive items are often (not always) better quality. As a result, they actually cost less to own in the long run than repeatedly buying cheap. This is only true when the extra cost buys extra quality, though. If the extra cost is due to buying a brand or a style, that doesn’t necessarily translate into savings.

- “Frequency of use is the underlying driver of performance.” This is obvious but easily overlooked. The more you wear something, the less its long-term cost. The $100 shoes you wear twice a week for a year are actually more cost-effective than the $50 shoes you wear once a month.

- “A wardrobe with nothing but favorite clothes sounds nice. It may also be the best in terms of cost performance.” Because the value of your garments is driven by “cost per wear”, the more you wear a given item, the more value you receive from it. This naturally means your favorite pieces are most cost-effective. The bottom line? Not only do you enjoy wearing your favorite pieces more than your other clothes, but these favorites also save you money.

Based on three years of data, Hoverfält has some advice for others.

Find what you need and love, then buy only that. Focus on cost per use, not on price. Buy only favorites. (Or, using Marie Kondo’s terminology, buy only those items that “spark joy”.) Try to buy only clothes that can be worn in a wide range of situations. Buy for the long-term. Take good care of your clothes. Know when to get rid of an item.

I think one reason I love this article (and project) so much is that it reinforces some conclusions I’ve already come to.

Now that I’ve lost thirty pounds, I can fit in my old clothes again. And now my closet is filled to the gills because it contains both skinny clothes and fat clothes. It’s a mess. I’ve been thinking about how to evaluate what to keep and what to discard, and Hoverfält’s article helped to provide some clarity.

This weekend, I’ll make a pass through my closet and drawers to get rid of (and/or store) the things I know I won’t wear. And who knows? When I’m finished, maybe I’ll make time to create a wardrobe spreadsheet of my own. It sounds like fun!

Recent Comments